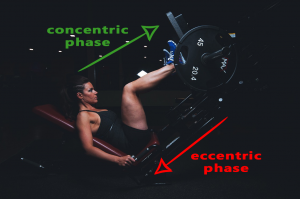

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (aka., DOMS) is something that shows up after we push our little body’s just a bit too far. While it isn’t something that is completely understood, the best explanation involves mechanical stress upon connective and muscle tissue, as a result of eccentric muscle contractions. Or, in other words, DOMS arises due to the contraction of muscles in the lengthened position.

You might be familiar with DOMS. You might relate it to mere muscle tenderness following a workout, or severe pain that has you reaching for the medicine cabinet. In either case, DOMS typically shows up in the window spanning hours to several days after strenuous exercise, and can last up to eight days. Any longer, and you might want to talk to your GP.

Dealin’ With DOMS: Revisited

To deal with DOMS, stretching is often prescribed. But does that make any sense? Not really.

Back in the day—1961 to be exact—DOMS was believed to be brought about from a mysterious substance known as “p.” This resulted in the development of the muscle spasm theory by Herbert A. Vries, and stated that exercise results in ischemia, which results in the “p” substance, which then stimulates nerve endings within the muscle, which then triggers spasms, which then causes more pain.

To counter this, static stretching was advised as a means for hindering this vicious cycle. But when other theories arose, like the muscle and connective tissue damage theories, the muscle spasm theory lost credibility. Yet, despite this, the stretching recommendation for the alleviation of DOMS lived on.

Of course, since muscles are viscoelastic—i.e., exhibit viscous and elastic properties—stretching and holding at a new length can indeed promote neural adaptation. That is, a certain stretch may initially be painful or difficult, but might eventually become relaxing. But that doesn’t have anything to do with preventing or recovering from DOMS, however.

Over and over again, static stretching has been found to have nothing to do with DOMS. In fact, prolonged stretching (60 seconds or more) may result in more soreness in the muscles due to further damage, and can even decrease performance capabilities if implemented prior to exercise.

Which doesn’t discount the fact that you simply feel better when you stretch, mind you. Or even knock down stretching as a method to not only get you off the couch and move, improve blood flow, or even help you adapt to new pain levels. But it is something to think about—especially if you are one to spend hours each day stretching that temple of a body you’ve got going on.

This all does raise the question, “should DOMS even be a goal in the first place?,” but perhaps I’ll leave that one for another time. Although, I have brushed over similar topics here and here.

Questions? Leave them below. Would you like to read the studies used in this article in full? Shoot me an email.