So we all know we have five senses; seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and feeling, right? But what many of you might not realize, a sixth sense does in fact exist.

And it’s not even an ‘I can see a dead Bruce Willis’ (shit; sorry, spoiler alert) sense.

A real one.

Proprioception.

What it is.

You may have heard of this proprioception word before. It’s talked about a fair bit when it comes to training. But let’s break it down anyway.

‘Proprio’ – coming from the Latin word ‘proprious’ meaning “one’s own”, is the word whacked onto the front of seven letters (c, e, p, t, i, o and n) to give the meaning for our sensory information as to where our limbs, trunk and head position are.

Basically, it is our self-perception of each of our joints in space and time and the movements that they participate in.

It’s one of the key reasons why we can move our hand to scratch the back of our neck without the aid of a mirror or a list of steps of how to go about this task.

We just know. And we sense how and how far we are required to move to scratch that itch (is anyone else itchy reading this?).

So, proprioception is created from received sensory information from our joints, but we can also add what is known as our tactile senses to the mix.

Tactile sense.

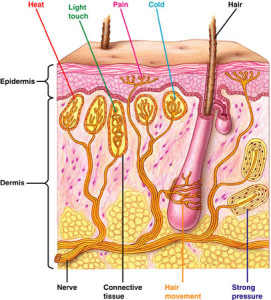

This relates quite well to proprioception, and can be explained as being the sensory information we receive from our skin mechanoreceptors that feel pain, temperature and movement.

These senses also contribute to our accuracy, consistency and force adjustment (think, ‘how hard do I have to squeeze this squishy key-ring to get the eyes to bulge out?’ sorta thing).

These senses also contribute to our accuracy, consistency and force adjustment (think, ‘how hard do I have to squeeze this squishy key-ring to get the eyes to bulge out?’ sorta thing).

So, proprioception and now skin mechanoreceptors, this shit is getting out of hand. Stay with me though, it’ll all come together.

Balance.

Balance is typically known as our neuromuscular (our nerves and muscles) function relating to cognitive and environmental factors surrounding us.

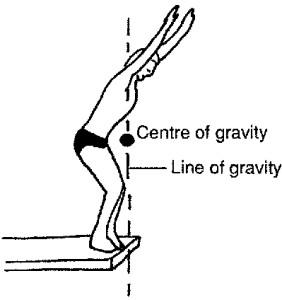

Solid objects have it easy; their balance is due to their center of gravity lining up with their base of support. We humans, on the other hand, have to deal with this damn stability thing on top of all of this.

Like life isn’t already hard enough with jobs, bills, taxes, blinking and breathing, right?

You might not think about it during most of your day-to-day activities, but every now and then, gaining or re-gaining stability is a required feat. And of course, it is mainly to stop us from falling over with a possible injury (or even death!) to deal with.

Anyway, this stability stuff we’re talking about goes quite well with balance.

It’s created due to our line of gravity and it’s relation to our base of support (feet, hands, head, back, etc.).

External disturbances can affect it, but we’re able to use our reflexive and cognitive movements to recover ourselves by stepping (think, being pushed in the side), swaying (think, surfing) or even the less attractive circumstance of flailing your arms around like a crazy person (think, trying to walk along a tightrope).

Okay, now that we’ve got all that out of the way, we can put it all together.

Okay, now that we’ve got all that out of the way, we can put it all together.

To define human balance simply, we can say it is the maintenance of our posture, our ability to move between postures, and how we react to external forces.

Cool? Cool.

Let’s move on.

Proprioception vs. Balance.

Since proprioception is our sense of awareness to where we are, and balance is the skill we must harness to prevent us from falling over, we can now tell the difference between the two quite easily.

Surprisingly (and sadly), we can’t actually improve our senses. Despite the fact that you may of heard of this being possible.

Let me put it into context before you hit that exit button.

Think of a wine taster; over time, their ability to define certain flavours improves. This in turn gives rise to them being able to say things like, “oh yes, this is a marvelous wine. The structure of it is impeccable and I can taste hints of strawberry and pineapple.”

It’s not necessarily their taste (or sense) that has actually improved, just their skill (or, palate) to pick up on certain flavours/scents.

They learn to differentiate between certain flavours/scents so that it’s not just a cluster of flavours resulting in, “mmm, it’s alright. Kinda, umm… Liquidy… I guess?”

Stable vs. Unstable.

Unstable surface training is kind of a sham. And the use of Bosu balls and Swiss balls literally originated from physical and occupational therapists implementing them into their training, with the intention to stimulate ankles and knees after injury/reconstruction for their rehabilitation clients.

For some reason however, the minor stimulation that occurs (which is perfect for the initial stages of rehab) snowballed into a mainstream craze that has people all around the world thinking that squatting on a Bosu will help them lose weight faster or build a stronger core due to an increase in muscle activation.

This isn’t further from the truth.

Studies have shown that there is literally no more muscle activation performing a squat on a stable surface, than there is standing on an unstable surface.

If we want more activation from all of our muscles (including the little stabilizing/“core” ones), then why would taking away a solid surface and putting ourselves on an unstable one produce more results?

If we can output more force into a stable surface, then more of our muscles will be stimulated.

And when more of our muscles are being stimulated, then of course, more gainz are to be had and more fat is to be lost.

But despite there being no more activation than a stable ground squat, your ability to stand on one of these things will of course improve over time. Although, this isn’t due to a better proprioception awareness or a stronger core however, or even a better balance/muscle activation reason.

It is simply due to your skill for standing upon a Bosu/Swiss ball improving.

Which means, you are only better at standing on a Bosu/Swiss ball. Nothing more. And unfortunately, not as strongly-cored as you might think.

However, this still opens up a new question if in fact this particular skill carries over to anything else in life.

Carry over.

Simple answer: no.

But since you asked so nicely, let’s break it down some more.

If balance is achieved by maintaining posture through the activation of muscles (or, strength and stiffness of certain joints), then why would training on an unstable surface help healthy/uninjured people get the most out of their training?

I don’t see too many athletes; or hell, even common peasants like ourselves engaging in walking, running, jumping, or even standing on unstable surfaces.

A surfboard can’t even be a valid argument when it comes to this due to it being pretty damn solid/stable, despite the fact that they’re typically used on water.

Sadly, training our proprioception for tasks is seriously impossible. And the only possible way of improving in certain things is by improving in certain skills in certain areas.

Again, take the wine taster: better at differentiating between smells/flavours. A surfer: better at swaying and regaining control in their posture. A Bosu ball squatter: better at standing on an awkward surface.

Real training.

As we’ve already discussed, balance comes down to being able to keep our posture intact through different situations and being able respond accordingly.

So, a couple of the best ways to train balance would seem to be closing our eyes when performing an exercise/skill/movement, and then reopening them to a huge stimulus/distraction to try and knock our posture out of whack.

This would be perfect to create more of a real life situation where we would have to switch on and off certain muscles to regain control over our posture.

Core training on the other hand, is better achieved when there is more activation in all our muscles. And this is where methods like single leg training can come into play.

One of the more popular methods (of course) is to simply increase the overall load in our training/exercises.

Since, when you compare a squat done on a Bosu to one done on solid ground with added weight, tell me your stabilizers aren’t switching on and providing you with a better environment for strength gains or fat loss when performing the stable grounded one.

___________________

REFERENCES.

Daehan Kim, Guido Van Ryssegem & Junggi Hong. Overcoming the Myth of Proprioceptive Training. Clinical Kinesiology.

Paul M. Juris, Ed.D. The Truth on Fitness: Should We Use Unstable Surfaces?. Cybex International.

James A. Ashton-Miller, Edward M. Wojtys, Laura J. Huston, Donna Fry-Welch. Can proprioception really be improved by exercises? Knee Surg, Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc (2001) 9 :128–136.

Simon C. Gandevia. Proprioception, Tensegrity, and Motor Control. J Mot Behav. 2014;46(3):199-201. doi: 10.1080/00222895.2014.883807.